Year 2013 in Review: Land, a Country in Crisis

Published on 21 March 2014As part of the lead-up to the release of our report “Human Rights 2013: the Year in Review,” LICADHO is publishing a four-part web series reviewing the key human rights events of 2013. Daily installments will be published throughout the week, culminating with the publication of our report on March 24.

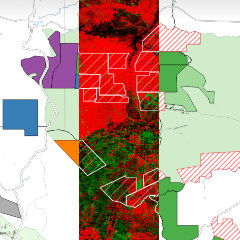

Elections aside, land remained the single most contentious issue in Cambodia in 2013, as it has been for at least the last 10 years. Over 2.2 million hectares of Cambodian land have been granted to large firms in the form of economic land concessions (ELCs). These concessions and various other land grabs have affected more than 420,000 Cambodians since 2003, according to investigations conducted by LICADHO.

In 2012, with commune elections looming and pressure from the donor community rising, the Prime Minister and his party proposed two solutions to the land crisis: First, a moratorium on new ELCs, along with a review of existing concessions, and second, an expedited land titling program designed to put more titles in the hands of rural people. As of the close of 2013, both programs have failed to live up their billing.

Although the so-called moratorium has slowed the pace of new ELCs, it did not totally stem the tide, with at least 16 new concessions granted since the ban was announced in 2012, totaling over 80,000 hectares. In 2013 alone, the land of almost 2,900 families was grabbed. More than 460 of these families were forcibly evicted.

Meanwhile, the promised “systematic review” has yet to materialize, and none of the well-documented problematic concessions have been cancelled.

The land-titling program has also sparked controversy. The program sent over 2,000 ruling party-affiliated youth volunteers to crisscross the country, measure land and issue titles. Implementation has also been shrouded in secrecy, and independent monitoring has been explicitly forbidden.

Although the government claims that it provided titles to over 470,000 families, covering 1.8 million hectares of land, the program meticulously avoided most areas of land conflict, where ELCs had infringed on the land of previous occupants.

Perhaps most troubling, however, is the fact that the program was funded by private donations from the Prime Minister and his closest allies: high-ranking members of the ruling CPP and business tycoons. In other words, the program completely bypassed established state institutions, leading some to call it a massive act of vote-buying.

In addition, there have been numerous credible reports of landholders, especially in indigenous communities, being intimidated or tricked into accepting terms dictated by the volunteer students. Such individual titles undermine extensive efforts to protect indigenous communities through communal land titling. There are also credible reports of landholders being told their new titles would be revoked if the ruling party loses the elections, or being told their official title would only be delivered after a successful election.

The development of the Cambodian sugar industry has been accompanied by violent forced evictions; widespread seizures of farmland; destruction of property, crops and community forests; and the use of violence and intimidation

SUGAR UNDER SCRUTINY

Cambodian sugar plantations – many of which are built on land violently wrested from poor farmers – were in the international spotlight throughout 2013.

Since 2009, an increasing number of ELCs have been used to produce raw sugar. This is directly linked to the European Union’s (EU) Generalized System of Preferences (GSP) preferential trade scheme, which allows Cambodia to export sugar to the EU duty free, specifically under its Everything But Arms (EBA) categorization.

Cambodia went from virtually zero sugar holdings in 2006 to more than 100,000 hectares under lease to agro-industrial firms for cane production in 2012. Since the liberalization of the EU sugar sector went into effect in 2009, the value of annual Cambodian sugar exports jumped from US$51,000 to US$13.8 million in 2011. Some 92% percent of exports went to the EU. Those who export the sugar have openly and repeatedly stated that they invested in sugar in Cambodia in order to be able to take advantage of EBA.

The development of the Cambodian sugar industry has been accompanied by violent forced evictions; widespread seizures of farmland; destruction of property, crops and community forests; and the use of violence and intimidation.

EU regulations set up human rights safeguards which require an investigation, and potentially the withdrawal of trade preferences, where serious and systematic human rights violations have been found. But thus far, the European Commission has not triggered these safeguards. In March, 13 Members of the European Parliament formally requested an investigation of ELC-related human rights abuses in Cambodia. The European Commission declined.

Meanwhile, a group of 200 villagers from Koh Kong province took matters into their own hands, launching a multi-million pound civil lawsuit against Tate & Lyle in the UK, claiming the sugar company knowingly profited from unlawfully seized land. Some 600 villagers from Oddar Meanchey province filed a separate complaint with the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand against Thai sugar giant Mitr Phol Sugar Corporation, which holds large concessions in Cambodia. Their case is still pending, as efforts to enforce the requirements are met with court inaction.

LOOKING TO 2014

At the end of a turbulent year, it may appear that little has changed in Cambodia; the old power structures remain in place and the government continues to bear down hard on any threats to its authority. But on the streets, things have changed. The people have mobilized themselves as never before and, despite the risks, refuse to be daunted. With neither side backing down, a peaceful 2014 is an unlikely prospect.

MP3 format: Listen to audio version in Khmer

- Topics

- Land Rights

- Related