Cambodia Should Register, Not Return, Vietnamese Asylum Seekers

Published on 1 May 2015; Joint OrganizationsCambodia’s refusal to allow asylum seekers from Vietnam to register and seek refugee status demonstrates a dismal failing to abide by international refugee law, LICADHO and Human Rights Watch said today. In the last four months, Cambodia has forcibly deported 54 Vietnamese asylum seekers, and appears poised to deport 40 more.

“Cambodia should immediately register the 40 Vietnamese asylum seekers who have reached Phnom Penh,” said Naly Pilorge, Director of LICADHO. “The government should ensure that the country is open to asylum seekers from Vietnam, and that they are allowed to register so that they can receive a fair and independent determination of their claims of persecution.”

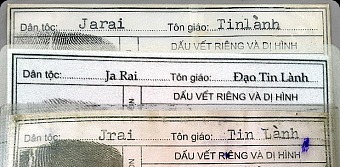

In March 2015, the Cambodian government recognized as refugees 13 ethnic and religious minority asylum seekers from Vietnam who had been brought to Phnom Penh in late 2014 with the help of the Cambodia office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. By contrast, since January 2015, it has refused to register as asylum seekers and to assess the claims for refugee status of around 100 other members of the Jarai and E De (Rhade) ethnic minorities – also referred to as Montagnards. These individuals left Gia Lai and Dak Lak provinces in the Western Highlands (Tay Nguyen) of central Vietnam, where they allege they have been subject to years of persistent religious and political persecution. In interviews with LICADHO and Human Rights Watch, they have in particular described persecution for their adherence to De Ga Protestant Christianity, which Vietnamese authorities deem a “wrong religion,” and because of suspicions that they are advocating greater political autonomy for ethnic minorities in the Western Highlands than the Vietnamese authorities allow.

The government should ensure that the country is open to asylum seekers from Vietnam, and that they are allowed to register so that they can receive a fair and independent determination of their claims of persecution.

Of these asylum seekers, 54 have been summarily deported by Cambodian police and authorities in Ratanakiri province, into which they had come from Vietnam. Forty other Jarai and E De have managed to make their way to Phnom Penh by various routes. Some of them have presented themselves to the government’s Refugee Department, but been told they cannot be registered. Recently, others have been told they will not even be allowed to present themselves for possible registration. Six of them are children, one a 15-month-old baby.

The government's initial decision to provide refugee status to 13 Jarai is recognition that persecution has been occurring in the Western Highlands. Nevertheless, it has since treated the Jarai and E De being refouled and otherwise refused registration as simple Vietnamese illegal aliens coming to Cambodia for purely economic reasons and as persons posing a threat to Cambodia’s national security or public order. They have even denied these Montagnards are members of an ethnic minority group. This has been reflected in repeated statements made by the Ministry of Interior and Ratanakiri province officials, which have offered no evidence to back up such contentions and cannot have been based on any attempt to assess the asylum seekers’ claims.

Cambodia ratified both the 1951 Convention relating to the Status of Refugees and its 1967 Protocol on October 15, 1992. The government’s position seems to be relying on the provisions of a December 17, 2009 sub-decree hastily promulgated to provide a basis for the forcible deportation three days later of 20 Chinese Uighur asylum seekers to China, in clear violation of Cambodia’s human rights obligations. The sub-decree grants the government’s General Department of Immigration, to which the Refugee Department is subordinated, a key role in deciding whether or not a person will enjoy asylum and refugee status. Although the sub-decree stipulates that an asylum seeker may place a request for asylum before the competent authorities and must thereby be considered as an applicant for asylum with the status of a non-immigrant alien, it does not require that the authorities allow them to temporarily enter or reside in Cambodia. On the contrary, it says the competent authorities are empowered to deny entry or expel asylum seekers if in the view of those authorities their presence “will adversely affect national security or public order.”

On April 29, 2015, Police Gen. Sok Phal, head of the General Department of Immigration, escalated the threat to the 40 Jarai and E De asylum seekers and also threatened to take action against United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). In Cambodia, UNHCR is mandated to pursue better refugee protection by supporting the government to develop its asylum system in accordance with article 35 of the 1951 Refugee Convention, which requires government cooperation with UNHCR and refers to a UNHCR supervisory role with regard to refugee matters.

Describing the 40 asylum seekers in Phnom Penh as “illegal Vietnamese immigrants,” Sok Phal declared “we will arrest those people if we see them because they crossed the border illegally.” He also accused UNHCR of conspiring with them and asserted that Cambodian “law says that any individual that has conspired with immigrants must be condemned.” Sok Phal’s statement suggests that the Cambodian government is threatening to invoke article 29 of Cambodia’s September 1994 Immigration Law against UNHCR personnel. This article provides for imprisonment of from three to six months of persons who “provide assistance to or help conceal the transport of” an alien who enters Cambodia “without authorization” and stays in the country “in hiding or disguise or by means of other subterfuges.” Invoking this law would not only ignore UNHCR’s mandate in Cambodia, but also the immunities enjoyed by UNHCR and other UN staff there under the terms of the 1946 Convention on the Privileges and Immunities of the United Nations, to which Cambodia is a party.

“If Cambodia’s donors don’t act immediately and forthrightly to stay the government’s hand, we may see a mass forced deportation even larger than that of the Chinese Uighurs in 2009,” said Brad Adams, Asia Director at Human Rights Watch. “This would be a disaster not only for those returned, but for human rights generally in Cambodia, and the government should know it will pay a big diplomatic price if it goes ahead with such an outrage.”

For more information, please contact:

▪ In Phnom Penh, Naly Pilorge (English): +855-12-803-650

▪ In Phnom Penh, Am Sam Ath (Khmer): +855-12-327-770

PDF: Download full statement

MP3: Listen to audio version in Khmer