Getting Away With It

Released in November 2016| Download this briefing in English (PDF, 576.04 KBs) | |

| Download this briefing in Khmer (PDF, 368.83 KBs) | |

| Listen to audio version in Khmer |

A year ago, to mark the 2015 16 Days Against Gender Based Violence campaign, LICADHO published a report Getting Away With It: The Treatment of Rape in Cambodia’s Justice System. The report was based on cases investigated by LICADHO in 2012, 2013 and 2014 and found that there were grave and systemic flaws in how rape cases are prosecuted in Cambodia and as a result, a disturbingly low number of convictions. There were several reasons for this: the extensive use of financial compensation to settle cases, widespread corruption amongst the police and the judiciary, poor understanding and application of the law by judges, and the prevalence of discriminatory attitudes towards women.

A year on from that report, this briefing carries out a similar analysis of the rape cases investigated by LICADHO in 2015 and finds that flaws in the justice system revealed by last year’s report remain largely unaddressed.

Overview of all cases

In 2015 LICADHO investigated 282 cases of rape or attempted rape, of which 125 are closed and 157 are still open. Of the cases that remain open, 38 date from the first quarter of 2015 which means that they have remained unresolved for nearly two years, an indication that the response of the criminal justice system to reports of rape remains slow.

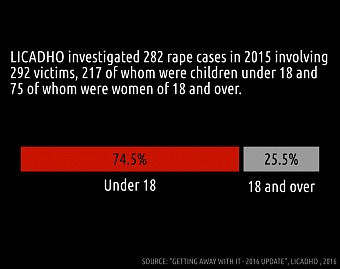

The 282 cases involved 292 victims, 75 of whom were women of 18 and over and 217 of whom were children under 18. The relatively low number of cases involving adult women is a trend that continues from the 2015 report and may be a result of under-reporting rather than being a true representation of the number of cases. Fear of social stigma and of blame and rejection by their husbands are particularly strong disincentives for adult women to report rape.

Of the victims under 18, 14 (6.5%) were between one and five years old, 76 (35%) were between six and 11 years old and 127 (58.5%) were between 12 and 17 years old. One case involved multiple male victims but all other victims were female. The percentages are very similar to those in the 2015 report which also found that 58% of child victims were aged between 12 and 17. This suggests that as children get older their risk of experiencing sexual violence increases and reaches a peak as they enter puberty.

Outcomes of all Closed Cases

As in the 2015 report, the analysis of closed cases involved first allocating them to three broad categories: those that ended at some point before trial; cases that went to trial but which ended without a conviction or with a conviction that was dubious; and cases which ended with a conviction for rape and a prison sentence compliant with the requirements of the Criminal Code.

Out of a total of 125 closed cases involving both women and children, 32 (25.5%) ended before trial, 40 (32%) ended with a trial followed by a flawed conviction or an acquittal, and 53 (42.5%) ended with a conviction and an appropriate sentence. Compared to the 2015 report, the percentage of cases closed before trial has decreased from 32%, the percentage of cases followed by a flawed conviction or an acquittal has dropped very slightly from 33%, and the percentage of cases for which there was a satisfactory conviction and an appropriate sentence has increased from 35%. The increase in satisfactory convictions is welcome but one year’s worth of data is not enough to conclude that it represents a trend. Moreover, an examination of the cases that closed before trial and those that ended with a flawed conviction suggests that all of the problematic attitudes and practices discussed in the 2015 report still persist.

Settlement by Compensation

As in 2015, cases which were settled by compensation made up the largest number in the category of cases which ended before trial; out of 32 cases, LICADHO monitors received information that 19 were settled by compensation in return for which the victim dropped the criminal complaint. Five of the cases involved women of 18 or over and 14 involved children under 18.

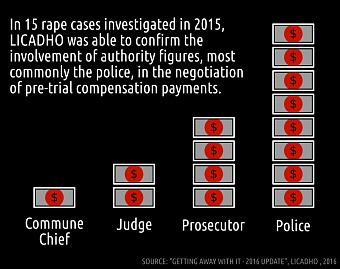

Compensation deals are often negotiated by authority figures after a case has been reported to them. In 8 of the 19 cases, the compensation was negotiated by the police, four were negotiated by prosecutors, two by investigating judges, and one was negotiated by a commune chief. Four appeared to have been negotiated by the families of the victim and perpetrator without any outside facilitation and in three of those cases, the victim and perpetrator were related.

When police and court officials help to negotiate compensation to settle a case, they almost always take a payment from the suspect and sometimes from the victim. Information about such payments is difficult to uncover because they are by their nature corrupt and all parties want to keep them secret but LICADHO monitors do occasionally hear about the details of a negotiation.

A 24 year old woman was raped after joining a relative’s wedding party. The suspect was initially arrested and the case was forwarded to the prosecutor. At this stage the victim agreed to accept $1,500 in compensation from the suspect in return for which she would withdraw her complaint. The suspect also agreed to give $3,000 to the prosecutor to ensure that he would not be charged. The prosecutor received the payment and the suspect was released but in this case the victim never received her compensation payment. It is possible that in this case the investigation judge also received a payment because it is he who has the power to detain or release suspects before trial.

Settlement of criminal cases by payment of compensation is not permitted under Cambodian law and police officers are potentially criminally liable if they prevent a criminal case from proceeding if a victim has withdrawn a complaint or if there has been a negotiated settlement between the victim and the suspect. Receipt of bribes by public servants and judges is also a criminal offence. And yet, LICADHO data and the experience of LICADHO monitors suggest that such practices remained commonplace in 2015 and are rarely, if ever, punished.

Marriage of the Victim to the Suspect

In 2015, LICADHO monitors received information that two cases were settled by the marriage of the victim to the suspect. As in the 2015 report, the number is low but the fact that it continues to happen at all is extremely troubling. It is an indication that the value attributed to women remains low and is largely attached to their sexual purity. Once this is perceived to be lost, even if it is through rape, for some women and girls, marriage to the suspect is seen as their best or only option.

A 12-year-old girl was raped three times by a 20-year-old man. Her family reported the case to the commune police who arranged a negotiation with the suspect’s family. The girl’s family agreed that she would marry the man as soon as she reached 16, the legal age for marriage, and withdrew their criminal complaint. It is likely that the police received money for facilitating the negotiation.

Indecent Assault

Of the cases that ended with a flawed conviction or an acquittal, ten began with a charge of rape by the prosecutor but ended with a conviction for indecent assault. The charge was changed either by the investigation judge or the trial judge. Indecent assault is a lesser offence than rape, punishable by one to three years’ imprisonment. Whilst in some cases there may have been legitimate reasons for the change, as was discussed in the 2015 report, it is often made because of a misunderstanding of the law on the part of judges or because of corruption. For example, six of the ten cases involved an act of rape that was interrupted by someone else or which was brought to an end because the victim fought back. In these circumstances, a conviction for indecent assault is a misinterpretation of the law and a conviction for attempted rape, which carries the same penalty as rape, is appropriate.

Medical examinations are often the reason that charges are changed. If a medical report states that there is no evidence of serious injury to the genitals or recent damage to the hymen, it is common for the court to conclude that the penetration of the vagina was not deep enough to count as rape and the suspect is charged with indecent assault. In many cases, medical reports are given disproportionate weight and other evidence is overlooked. Furthermore, because the reports are so decisive, suspects sometimes pay bribes to medical examiners or local health departments so that they will understate the victim’s injuries.

A seven-year-old girl was raped three times on different occasions by a neighbour. The suspect was charged with rape by the prosecutor and this was confirmed by the investigation judge. However, at trial the judge changed the charge to indecent assault because the medical exam showed no damage to the genitals. The perpetrator was sentenced to two years in prison.

Age of victim

In nine cases in which the victim was a minor, the perpetrator was convicted of rape but given a sentence which did not take account of the minority of the victim. According to Cambodian Criminal Code, it is an aggravating circumstance to the offence of rape if it is committed against a person who is vulnerable by reason of their age. Where rape is committed with aggravating circumstances the penalty is seven to 15 years’ imprisonment. Where it is committed without aggravating circumstances, the penalty is five to ten years’ imprisonment. In the nine cases, the victims were between nine and 14 years of age but the perpetrator was sentenced to only five years’ imprisonment. This suggests that some judges are not fully aware of the provisions on rape in the Criminal Code or are not giving due consideration to aggravating circumstances when passing judgment.

Suspended sentences

In six cases, the perpetrators were convicted but given partially suspended sentences. Prison sentences may be suspended if they are of less than or equal to five years and if the accused has not been sentenced to a term of imprisonment in the previous five years. Otherwise there is no guidance on when and why suspended sentences should be given. This means that if there is a minimum five-year sentence for rape, or if aggravating circumstances are not taken into account, or if the charge is changed to indecent assault, a perpetrator’s sentence may be suspended. This can result in some very low sentences. Four of the six cases which ended with suspended sentences involved victims who were minors and two began with charges of rape which were changed to indecent assault by the investigation judge. Suspended sentences are often the result of corrupt payments to judges.

A thirteen-year-old girl was attending a neighbour’s wedding. When she left the party to go to the toilet, she was raped by another guest, a man in his 20s. At trial the perpetrator was convicted of rape but despite the victim’s age, was sentenced to only five years in prison. The sentence was then partially suspended and the suspect had to serve only 16 months in prison. Had the victim’s age been taken into account, the suspect would rightly have been convicted of rape with aggravating circumstances and sentenced to a minimum of seven years in prison. Suspension of the sentence would then not have been possible.

Acquittal

In three cases, there was a trial followed by a finding of innocence. It is quite proper that some cases should end in this way, however, in two of the three cases there were reasons to doubt the validity of the outcome. In one case the finding of innocence came after the victim agreed to receive $500 compensation. According to the victim the judge received $3,500 from the suspect in return for acquitting him. In one other case, the trial judge questioned the victim about her sexual history and concluded that as she had had sex with a number of men previously, she must have given her consent on the occasion in question.

Conclusion

LICADHO’s 2015 report on rape, based on cases investigated in 2012, 2013 and 2014, brought to light the failure of the Cambodian justice system to properly investigate and punish cases of sexual violence against women and children. This briefing, based on cases investigated in 2015, indicates that the factors contributing to that failure of the justice system – corruption, discriminatory attitudes towards women and girls, misunderstanding of the law and lack of resources – persist, and that for the majority of victims of sexual violence, justice remains at best partial. The Cambodian government must take steps to bring about the justice system reform and attitudinal changes necessary to address the current failings, as outlined in the recommendations in the 2015 report. Until it does so, there will be no end to impunity for perpetrators of rape and no justice for their victims.

For more information, please contact:

▪ Ms. Nap Somaly, Senior Women's and Children's Rights Monitor, mon4@licadho-cambodia.org, +855 (0)12 251 118 (Khmer)

▪ Ms. Naly Pilorge, LICADHO Deputy Director of Advocacy, advocacy@licadho-cambodia.org, +855 (0)12 803 650 (English)

.jpg)